In an interconnected world, consumers often face a dilemma: should they choose locally produced goods or opt for products made elsewhere? The environmental impacts of this decision aren’t always straightforward. Whether it’s food, furniture, electronics, or clothing, the sustainability of a product depends on various factors. In this article, we’ll explore key considerations for evaluating the sustainability of local vs. non-local products and and how to make informed choices for both goods and food. We’ll also integrate insights from The Locavore’s Dilemma, a book that challenges common assumptions about local purchasing.

How a product is made has the largest impact on its sustainability. This applies equally to food and manufactured goods.

Example: A locally made chair using uncertified timber may contribute to deforestation, while a globally sourced one from FSC-certified wood could promote responsible forestry practices.

Transportation is an essential factor in the sustainability of both goods and food. While local products travel shorter distances, the transportation method is critical in determining emissions.

Example:

A jar of local honey delivered in small vehicles to multiple locations could produce more emissions than honey shipped internationally in a single bulk shipment.

Economies of scale influence the environmental impact of production. Larger operations often optimize resource use, reducing the footprint per unit, whether the product is food or goods.

Example:

A local clothing brand might produce fewer garments but require more water and energy per piece compared to a larger factory using advanced, water-efficient dyeing processes.

This applies primarily to food but can also affect the production of certain goods. Producing items locally during their natural season or availability is often more sustainable.

Example:

Opting for seasonal fruit or a product made with freshly harvested materials minimizes the energy required to store or transport the item over extended periods.

Labels like “organic,” “Fair Trade,” or “sustainably sourced” provide transparency about how goods and food are made. These certifications apply universally to help consumers make environmentally responsible choices.

Example:

A locally produced chair without FSC certification may harm forests, while a non-local option with an FSC label ensures sustainable forestry practices.

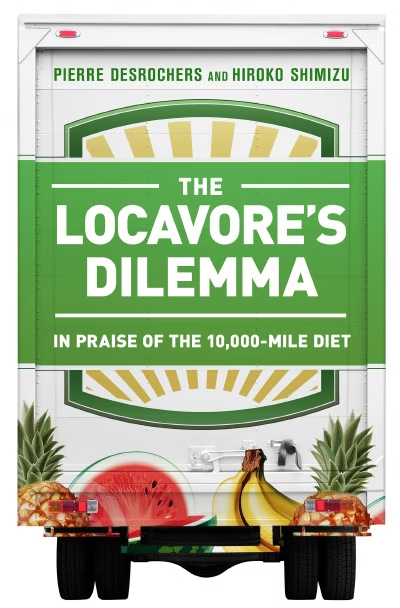

The Locavore’s Dilemma: In Praise of the 10,000-Mile Diet by Pierre Desrochers and Hiroko Shimizu offers a thought-provoking view on the local vs. non-local debate. It challenges the assumption that buying local is always the most sustainable choice. The authors explore the complexities of global trade, production efficiency, and transportation impacts. They argue that proximity is just one factor in sustainability.

While the book focuses mainly on food systems, its insights also apply to goods. It examines specialization, economies of scale, and efficient logistics. These factors show how global systems can sometimes outperform local options in reducing environmental impacts. The book encourages readers to evaluate products—whether food, furniture, or electronics—based on their full lifecycle, not just their origin.

One of the most counterintuitive arguments in The Locavore’s Dilemma is that transportation—often perceived as a significant contributor to environmental damage—might not be as impactful as we assume. The authors highlight that bulk shipping methods, such as cargo ships and freight trains, are incredibly efficient in terms of emissions per kilogram of product transported.

This efficiency stems from the scale at which these transportation methods operate. For example, a single cargo ship can transport thousands of tons of goods across oceans with a relatively small carbon footprint per unit. In contrast, local transportation often involves smaller vehicles, like vans or trucks, which may have higher emissions per unit due to limited capacity and repeated trips.

Desrochers and Shimizu argue that focusing solely on transportation distance overlooks these efficiency differences. They emphasize that a product’s environmental footprint is influenced more significantly by how it’s produced and transported than by how far it travels. This challenges the common perception that “local is always better” and underscores the importance of examining the entire supply chain.

Example:

Shipping oranges from Spain to colder regions might have a smaller carbon footprint than growing them locally in energy-intensive greenhouses. Similarly, a phone assembled abroad and transported via cargo ship may be more sustainable than assembling components locally with inefficient logistics.

Specialization—the concept of focusing on what a region or industry does best—is a cornerstone of sustainable production. In The Locavore’s Dilemma, Desrochers and Shimizu argue that allowing regions to specialize in products they can produce most efficiently minimizes environmental impact.

Specialization takes advantage of natural resources, expertise, and climatic conditions. For instance, certain areas are naturally suited for specific industries due to factors like geography, climate, or resource availability. Forcing local production of goods that a region isn’t suited for often requires additional resources, such as energy-intensive methods or costly materials, which negate the benefits of reduced transportation.

Trade, therefore, becomes a tool to distribute products globally in a more environmentally responsible way. By enabling specialized regions to produce goods efficiently and share them with others, trade reduces the overall resource strain on the planet. This principle applies to everything from agricultural products to industrial goods, illustrating how interconnected systems can enhance sustainability.

Example:

Italy specializes in high-quality ceramics, while wool production thrives in New Zealand. Choosing these non-local goods can be more sustainable than forcing local production that requires more resources.

The idea that fewer transportation miles automatically equates to greater sustainability is a common misconception. Transportation is just one part of a product’s lifecycle, and factors like production methods, material sourcing, and end-of-life disposal often have a more substantial impact on the environment.

For example, a locally produced desk might seem like the greener choice, but if it’s made from wood harvested without sustainable practices, its environmental cost could far outweigh the transportation savings. In contrast, a desk made abroad using recycled materials or certified sustainable wood may have a smaller overall footprint, even with the added transportation.

Example:

A locally crafted desk made with uncertified, clear-cut timber from a nearby forest may result in deforestation and habitat loss. Meanwhile, an imported desk crafted from recycled or FSC-certified wood may have a lower net impact, even if it has traveled thousands of miles to reach the consumer.

Large-scale global trade networks often achieve efficiencies that smaller, local systems cannot match. These efficiencies come from optimized supply chains, advanced manufacturing technologies, and streamlined logistics. Larger systems can spread fixed costs like energy for production or transportation over more units. This reduces the per-unit environmental cost.

Global manufacturers also have access to better recycling and energy recovery systems. This reduces waste and emissions throughout the production cycle. In contrast, smaller, local systems may lack the resources to implement such technologies effectively. This can lead to higher energy use and more waste.

Example:

Consider a laptop produced in a cutting-edge global factory using energy-efficient systems and advanced emissions recovery technology. This laptop may have a lower overall environmental footprint than a locally assembled version. The local assembly might rely on outdated processes, consume more energy per unit, and create more waste—even if the final product travels a shorter distance to reach the consumer.

Choosing between local and non-local products is rarely straightforward. For both food and goods, sustainability depends on production methods, transportation efficiency, economies of scale, seasonality, and certifications. Insights from The Locavore’s Dilemma highlight the importance of looking beyond proximity to understand the broader environmental context.

By balancing these factors, you can make informed, environmentally responsible decisions that support sustainability, whether you’re buying a locally crafted table or an internationally sourced smartphone. Websites like Ethical Consumer can help you find sustainable brands that align with your values.

Further Reading:

Discover Sustainable Solutions at Ecotlas

At Ecotlas, we’re committed to supporting your journey toward sustainable living. Explore our curated selection of eco-friendly products designed to make green living accessible and enjoyable. Together, we can make a difference.

Get the latest tips, product recommendations, and eco-friendly lifestyle inspiration straight to your inbox. Join our community and take the next step in your journey toward a greener future.

We noticed you're visiting from Italy. We've updated our prices to Euro for your shopping convenience. Use United States (US) dollar instead. Dismiss